Old Manse

I hate quotation. Tell me what you know. — Ralph Waldo Emerson

We arrived in Concord close to midnight on a cool December night. Cool and damp; nowhere near the New England cold we expected for the first week of the last month of the year. And so the fog rolled in, thick and opaque, drifting through the trees and along the pavement. We felt transported, as if the road and the fog were rolling us back a hundred and fifty years, when some of the greatest American writers were alive and living in a sleepy little town outside of Boston. I would not have been surprised to see a horse drawn carriage clopping up the road, or a headless horseman dashing past in pursuit of a schoolteacher.

Concord hid in the fog and the trees, and it took us a moment to understand what the tiny, delicate floating lights behind the hazy mist were. Houses, all around us, lit not by street lamps but by candles in the windows. No other holiday decorations appeared out of the fog; not until we reached downtown.

We carried our bags up to the Colonial Inn, located in the heart of Concord, proudly declaring its rich and lengthy past stretching back to 1716. The foyer was quiet and still at midnight, decorated for the holidays in frosty white lights, evergreen boughs, and red velvet bows. Even though I knew quite well what year it was, that feeling of dislocation and transference remained; I wasn’t tethered to the 21st century. The Colonial Inn creaked and groaned with its age, and our second floor window overlooked streets empty of cars and lights strung through naked trees, casting a glow on closed shopfronts.

Concord settled in me like a slow moving fog, and I welcomed it.

We ate breakfast at the inn’s restaurant before setting out. The day was still remarkably mild for December, and our light winter jackets were more than sufficient. Our destination was only a short drive away, and the wooden bridge and the house were easy to locate.

Old North Bridge first.

We met the Minute Man by the bridge, tall and timeless and crafted from the metal of seven Civil War cannons by Daniel Chester French. He, along with a replica of the original bridge, went up in 1875, one hundred years after the Revolutionary War began by the quiet banks of the Concord River.

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard round the world.

The opening stanza of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s poem, “Concord Hymn,” is etched in the granite underneath the Minute Man. At the North Bridge Skirmish, on April 19, 1775, Minutemen and non-Minutemen militia faced off against British light infantry in a battle that may have sparked the beginning of the Revolutionary War. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s father, a child then, watched it happen from their home.

We imagined it on a quiet morning along the bridge, 240 years later.

Once the chill started to seep through our jackets, we turned to the lone, Georgian clapboard brown house nearby. Its windows faced the river and the bridge, giving its inhabitants an uncomfortably close view of what occurred here. Old Manse waited patiently, and we went to meet it.

A sign outside promised us hot cider and cookies, and we were not disappointed when we entered the gift shop and enjoyed the warm beverages before our tour began.

One hundred years after the Revolutionary War, Old Manse housed the authors that would help spawn a literary and philosophical movement—Transcendentalism. Bronson Alcott, Margaret Fuller, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson gathered in Old Manse to speak of their ideals. Their conversations and the creativity crafted in those rooms gave the house a weight, deepened the creaks of the old floorboards, and infused every antique and scrap of wallpaper with the whispers of their bygone discussions.

Old Manse was built in 1770, and much of the furniture and fine china are originals from the home, or very close replicas. We passed through the kitchen, into the lady’s parlor with its pink wallpaper, and through the foyer where a piano sat. Immense bookcases lined the wall of the landing on the second floor, the volumes giving off the musty smell of aged paper and book spines that would crack like old bones if opened. Each shelf could be removed, built for preservation instead of practicality; if there had been a fire in the home, the books could be lifted from the bookcase in rows and tossed out the second story window to save them. Mass book production didn’t begin in the U.S. until the invention of the steam-powered rotary printing press in 1843; beforehand, book production was more laborious, and so books were a far more precious commodity. A book collection was not so easy to replace.

We entered the study where Ralph Waldo Emerson penned the first draft of Nature, the 1836 essay that served as the foundation for the belief system of Transcendentalism.

The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs?

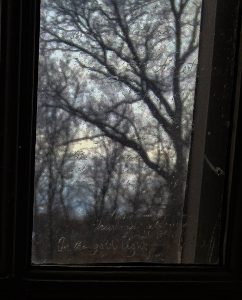

In another room, we found evidence of another notable literary figure’s presence at Old Manse; the desk where Nathaniel Hawthorne sat to write a collection of short stories, as well as the introduction to The Scarlet Letter.  Nathaniel and his new bride, Sophia, spent the first few years of their marriage as renters in Old Manse. They wrote letters to one another in the very windows of the house, sweet lines of poetry carved into the glass with Sophia’s diamond wedding ring.

Nathaniel and his new bride, Sophia, spent the first few years of their marriage as renters in Old Manse. They wrote letters to one another in the very windows of the house, sweet lines of poetry carved into the glass with Sophia’s diamond wedding ring.

We admired the dressing gowns laid out in the upstairs rooms, the narrow beds and fainting couches, the old badminton rackets, the wooden bassinet at the foot of a bed. I could picture Ralph Waldo Emerson rattling through these rooms, writing in his commonplace book and drafting essays and radical ideas for new modes of thought. When we were nearly done exploring Old Manse, we paused in the lady’s parlor again, and met the mildly uncomfortable gaze of a stuffed owl in a glass case that also made an appearance in an old black and white photograph on the wall. What conversations and interludes had this old owl seen and heard through the years?

When we left, we passed the heirloom vegetable garden that Henry David Thoreau had originally planted for Nathaniel and Sophia, as a wedding gift. No other place in Concord had given us the sense of close community like Old Manse had. We had no trouble seeing how an entire movement was birthed here, with so many great minds and literary geniuses living near one another and supporting each other’s writing.

Sitting on the banks of the Concord River and surrounded by the weight of important historical events, it was easy to see how Old Manse provided the perfect inspiration for such moving literature.

Our travels were not finished. We still had a certain pond, a family home, and a cemetery to visit.